Puerto Rico is facing a health care crisis after chronic mental and physical health issues often went untreated in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. Many doctors have left the island, but one volunteer group isn’t going anywhere.

Long-term risks

While Hurricane Maria no longer makes headlines every day on the U.S. mainland, Puerto Ricans are still recovering physically and emotionally from the island’s most devastating storm in decades. Doctors and medical professionals are needed more than ever.

Even before the storm, Puerto Rico’s financial crisis had driven doctors away from the island in search of jobs elsewhere. Between 2006 and 2016, 5,000 doctors emigrated from the island. An estimated 10 doctors have left the island per day since the storm, according to local news outlet El Nuevo Día, furthering the medical care crisis.

“Everything was so disrupted that their income stopped; their offices were destroyed,” said Dr. Wendy Matos, executive director of the University of Puerto Rico's School of Medicine faculty practice plan. “It’s like the rug was taken out from under their feet. People made decisions to survive.”

Those who remain are picking up the pieces.

“You have to go out to serve,” said José Luis Vargas Tapia, the leader of Iniciativa Comunitaria’s brigades, called “Iniciativas de Paz.” His father, José Antonio Vargas Vidot, started Iniciativa Comunitaria in 1990.

“You have to do it, because if not you, then who is going to do it?”

“You have to go out to serve. You have to do it, because if not you, then who is going to do it?”

José Luis Vargas Tapia, the leader of Iniciativa Comunitaria’s brigades, called “Iniciativas de Paz

As the sun rose in Toa Baja on a Wednesday morning in March, the clinic brimmed with volunteers preparing to set off on the mission.

They packed duffle bags full of medications and supplies, such as blood sugar monitors, vaccines, antibiotics. Franchely Soto, Iniciativa Comunitaria’s logistics coordinator, darted around volunteers with a clipboard, checking off her list with precision.

Things weren’t always so organized. To set up a clinic in nine days, they had to make do with the facilities and limited supplies they had at the time. The clinic inhabits one of the rooms in the preschool, and several other classrooms hold supplies, including the one where Morales sleeps.

Stethoscopes hang on plastic hooks, Post-its and papers plaster the walls, and the staff sit at card tables. A curtain divides the waiting area and administrative offices from where patients are seen.

In front of the door, a sign greets patients: “We are a big hug.”

The brigade has been on nearly 70 missions, and they have the process down like clockwork.

Day in the Life of a Brigade

Since Hurricane Maria, Iniciativa Comunitaria has helped more than 6,000 people in Puerto Rico between its clinic and its brigades. Explore a typical day brigade shift and night brigade shift.

Click on the clock to see the daily activities.

11:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m.

Rotating brigades return to homebase for a lunch break and to restock needed supplies.

12:30 – 1:30 p.m.

Brigades go back to finishing rounds in the community.

1:30 – 2:30 p.m.

Brigade workers provide medical consultations and care, encouragement and a sense of community.

3:30 – 4:30 p.m.

Brigade workers provide medical consultations and care, encouragement and a sense of community.

2:30 – 3:30 p.m.

Brigade workers provide medical consultations and care, encouragement and a sense of community.

4:30 – 5:30 p.m.

Brigades prepare to return to the home base from community sites. Brigade leader shares a summary of the day and thanks the workers for their engagement.

Brigade workers break down home base and board bus for the main clinic. This can take up to four hours.

Home around 9 p.m.

Initiativa Comunitaria's on-location health brigades offer medical care and encouragement

5:30 – 6:30 a.m.

Brigade organizer leaves home and calls other leaders to see if anyone has difficulty getting to the main clinic, where the day's group will meet.

6:30 a.m.

The main clinic springs into action. Workers load supplies onto the bus which will take them into the community for the day. Leader reviews best ways to help.

7:30 – 8:30 a.m.

Workers board bus and ride to the clinic's home base for the day. Locations are anywhere from 15 minutes to a couple of hours away from the main clinic.

8:30 – 9:00 a.m.

Tents and stations are set up.

9:00 – 11:30 a.m.

People start arriving at the clinic's home base of the day.

9:00 – 11:30 a.m.

Brigades leave home base to offer care to bedridden patients whose names are listed by the community organizer.

Vargas Vidot, who is now a senator in the Puerto Rican legislature, started Iniciativa Comunitaria to provide education and treatment for HIV and AIDS for at-risk groups. The program has grown to offer services in five different categories, including addiction and substance abuse, health education and international projects.

Around a year after he was elected in November 2016, his son, José Luis Vargas Tapia, took over leading Iniciativa Comunitaria’s brigades.

Vargas Tapia gathers around 20 volunteers for their morning briefing: doctors, medical students, nurses, administrators and anyone else who happens to be on hand that day.

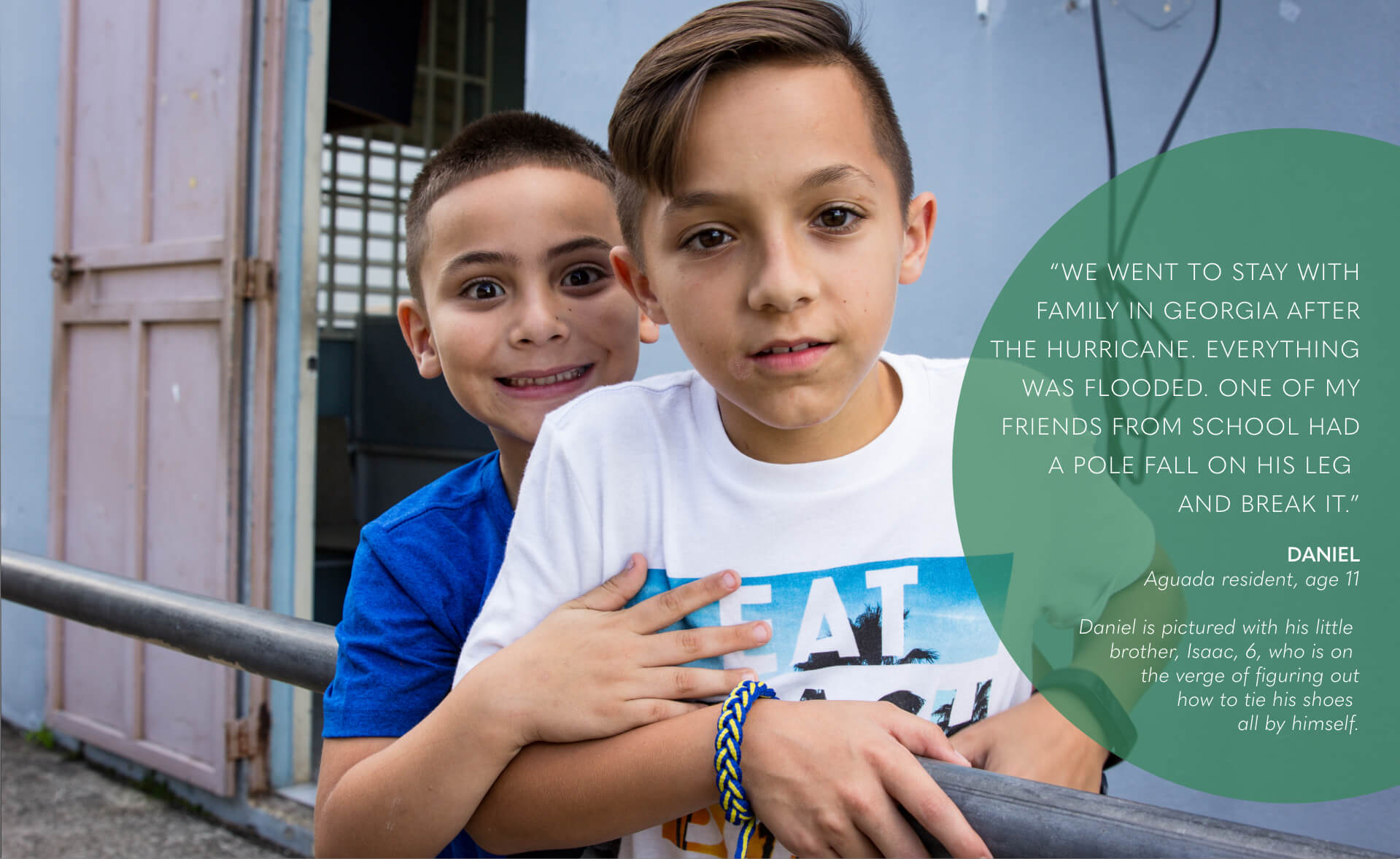

The community they’re about to serve—Aguada, a small town on the island’s west coast—is more than 70 miles away, but Vargas Tapia talks about patients whom he’s never met like they’re family. Some still don’t have power or water. Fallen trees still line many roads.

“Here we have no titles; here we are human beings serving other humans,” Vargas Tapia told the volunteers. “That's it.”

The volunteers load into a caravan of cars and set off through the countryside, watching as the buildings of San Juan give way to lush rolling hills, where Aguada overlooks a valley and a glimmer of the coastline.

After unpacking their supplies in the hot sun, Vargas Tapia and his team split up to visit patients, some of whom are bedridden. They have 37 people on their list.

One of them is 86-year-old Isidra Pérez Feliciano. Iniciativa Comunitaria’s van pulled up to her house, and a doctor and nursing student hopped out.

Pérez Feliciano, who is bedridden, has suffered from multiple ailments, including severe bronchitis, Type 2 diabetes, hypertension and ulcers. A lack of electricity can be life-threatening for the elderly population, so after losing power in the storm, Pérez Feliciano’s family used their generator between five and seven hours per day for five months to run the air conditioning.

They only ran the generator in bursts, but the cost of the gasoline to fuel it added up quickly. The family struggled to afford the near $1,000 cost.

Pérez needed to be taken to the hospital not long after the storm hit, but because the roads were blocked with debris, there was no way to get to the hospital. Her family struggled to keep her healthy in the long weeks with no power or access to medical care. Luz Bonilla, Pérez’s daughter, was finally able to heal her mother using natural remedies.

“At the beginning you feel desperate: no water, no light, no this, no that,” Bonilla said. “But little by little you say, ‘hello, this is something I can overcome,’ and little by little we settled.”

“At the beginning you feel desperate: no water, no light, no this, no that, but little by little you say, ‘hello, this is something I can overcome,’ and little by little we settled.

Luz Bonilla

Because Bonilla works at a local hospital, she was able to get in touch with her doctor and take care of her mother, but others still struggle to access medical care.

Although hospitals are open now, in the storm’s wake, they faced supply shortages, and Vargas Tapia said some hospitals turned away patients from other areas. He and other volunteers said some patients experienced long wait times to receive treatment.

But it’s patients with long-term diseases like diabetes who are most at risk, yet Matos said specialists she works with at the University of Puerto Rico’s School of Medicine have seen fewer patients since the storm.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 16 percent of Puerto Ricans reported having diabetes in 2014, compared to 10.1 percent for the U.S. population as a whole. A study from the University of Puerto Rico’s Medical School found that nearly 40 percent of adults in San Juan suffered from hypertension.

And a loss of power for some diabetics can be a life or death situation, as insulin needs to be refrigerated.

“The deaths after a disaster come from untreated chronic illnesses,” Vargas Vidot said. “So diabetes is endemic here. Hypertension is endemic. Cardiovascular problems are endemic.”

Chronic illness fatalities aren’t reflected in the storm’s death toll, even if many wouldn’t have happened otherwise. And Matos said there are other long-term health consequences that often get overlooked, such as mental health issues and suicide risk. The number of deaths by suicide increased by 29 percent between 2016 and 2017, after years of decline.

Other mental health conditions have likely been impacted too. A 2012 study of inner city primary care patients in Puerto Rico found that 14 percent had probable post-traumatic stress disorder.

While it’s too early for most research to track the long-term impacts Hurricane Maria could have had on PTSD, research on Hurricane Katrina can provide clues. A study of low-income parents in the 18 months following Hurricane Katrina found that nearly half exhibited signs of probable PTSD.

“The government disregarded the effect of a disaster on the emotional state of people,” Matos said. “That affects directly not only the thinking process and decision making, but their physical conditions too.”

“The young people are the future and if they are leaving, what’s gonna happen? Puerto Rico needs more young people to rebuild.”

Carla Santiago, a third-year medical student at the University of Medicine and Health Sciences on St. Kitts island and a volunteer with the brigade

During their brigades, the volunteers keep that concept in mind, focusing on both emotional and physical health. One volunteer plays guitar for the patients. It’s a remedy for the loneliness the increasing number of elderly face.

Between 2014 and 2016, the share of the population older than 65 increased from 14.5 percent to nearly 19 percent while the share of people under 18 declined, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

Since the storm, experts say it’s only gotten worse. While it’s difficult to track exactly how many Puerto Ricans have fled the island, estimates indicate that several hundred hundred thousand have arrived on the mainland. Most of them are the island’s youth.

“The young people are the future, and if they are leaving, what’s gonna happen?” said Carla Santiago, a third-year medical student at the University of Medicine and Health Sciences on St. Kitts island, who doubles as a volunteer with the brigade. “Puerto Rico needs more young people to rebuild.”

Sometimes, the elderly just need someone to talk to, or share a song with. And that’s where Iniciativa Comunitaria comes in.

Photo: Alexis Fairbanks

Photo: Alex Kormann

Photo: Alex Kormann

Photo: Alex Kormann

Photo: Alex Kormann

Photo: Alexis Fairbanks

Photo: Alexis Fairbanks

Photo: Alex Kormann

Photo: Alexis Fairbanks

Photo: Alex Kormann

Photo: Alexis Fairbanks

“Forgotten”

As Inciativa Comunitaria’s daytime volunteers pack up and head back to Toa Baja, the night brigades are just getting started.

The group of undergraduate and medical students at the University of Puerto Rico is part of Recinto Pa’ la Calle, a program that collaborates with Iniciativa Comunitaria that provides services at night for people who are homeless and drug users.

After loading cars with supplies, the volunteers pulled their cars up to an empty bus station, where just one other car was parked. Adriana Rodriguez, a third-year medical student at the University of Puerto Rico, hopped out of her car and approached a homeless camp, scattered with tents, mattresses and bicycles.

The camp’s residents brightened as she shouted, “Hola, Iniciativa!” from her car. After exchanging a few words with them, Rodriguez waved to her peers, who emerged from a caravan of cars donning Iniciativa Comunitaria’s logo.

The students handed out orange juice, coffee, sandwiches, clothes, toothpaste and condoms — anything they had in their supply of donations, they provided. Several of the students dressed wounds, while others just took time to listen to the stories of people in the camps.

René, who asked that his last name not be used, is the leader of this homeless camp. The other residents call him “the Veteran.”

René’s been homeless for years, but his four children have never been far away. His two daughters left for New York after the storm destroyed the roof of their home.

His daughters are receiving government assistance, but René said the Puerto Rican government hasn’t done anything for the people his homeless camp.

The members of the camp survived the storm thanks in part to Iniciativa Comunitaria’s volunteers, who brought them and others to a temporary shelter at the group’s headquarters.

Volunteers dropped off René and the others at the camp two days later. The storm destroyed what few things they had. Some of their mattresses were strewn against the fence along the other side of the wide lot. The bus terminal they rely on for light was without power.

But still, René stayed.

“I would be leaving all my people behind,” he said. “People need me to be here.”

The camp members have new belongings now, and the power returned a month later.

During the storm, many of Puerto Rico’s homeless stayed on the streets. It’s the homeless, the elderly, drug users and other “forgotten” populations that Iniciativa Comunitaria focuses much of its efforts on. And many of those residents and volunteers alike say government assistance is not reaching those who need it most.

“Most patients we have been seeing, they haven’t been seen by any physician or any group,” Soto said.

Many of those communities are used to helping themselves. Cantera, an impoverished community in San Juan recently visited by the brigade, has operated as a nonprofit for years, as have several others. The nonprofit leaders helped coordinate Iniciativa Comunitaria’s visit and identify patients.

“There’s a concept of community that doesn’t represent a geographic thing,” Vargas Vidot said.

That’s what drives Iniciativa Comunitaria’s volunteers to rebuild their community—whether it’s a town on the opposite coast of the island, a poor neighborhood in San Juan or a bus station just outside of the University of Puerto Rico’s medical school where the homeless sleep.

“We saw Puerto Rico literally broken,” said Sofia Muns, a first-year medical student at the University of Puerto Rico. “If you see something broken, it’s human that you want to bring it back together.”